This is an audio link to The Canterbury Tales: "General Prologue" read in the original Middle English.

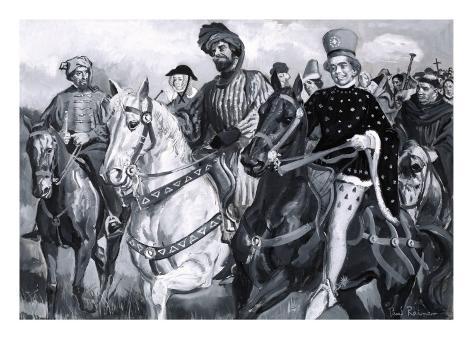

Geoffrey Chaucer’s The

Canterbury Tales:

“The Miller's Tale”

Chaucer wrote the collection of stories known as The Canterbury Tales in the 14th century as a poetic satire (Character). The beauty of the work is that just about every kind of class is represented from the time period and each is made fun of with just as much vigor as the next. Chaucer did not discriminate when it came to exposing embarrassing (and often times ironic and realistic) situations in his poetry. Satire was Chaucer’s way of criticizing the behaviors of the society in which he lived. He uses the humor of his satire to soften the blows of his criticism, especially towards those in power politically, which allows him freedom from fear of possible retribution. His use of irony is effective in that it appears in a way that is not necessarily overtly offensive. Yet, there is often a scathing analysis hidden behind the charmingly naïve narrator’s descriptions. The style of Chaucer’s poetry is incredibly useful in that it creates a flow in the words that is both easy to follow for the commoner and generally fun to read. It is through Chaucer’s intentional blend of these two flavors, style and irony, that he creates life out of stationary word-art.

In The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer uses a particular style of poetry throughout all 17,000 lines of the work (Canterbury). The compilation is written in iambic pentameter, in the dialect of the commoners—Middle English—as opposed to Latin or French, which were the languages of scholars and nobles of the period (Words). The lines are written using “open heroic couplets,” or “riding rhymes.” This form of rhyming scheme is of unknown origin, but Chaucer is thought to be the first to have used it extensively (Britannica.com). The use of this form of rhyme is so moving because it creates an interesting sound when read, much like the rhythm of a heartbeat, or the joyful bounciness of a gospel hymn. Its exciting style is part of what hooks its readers and leaves them with an aftertaste of laughter.

The irony in The Canterbury Tales is hysterical if only for the offhanded glide it makes into each flowing couplet in which it appears. Chaucer’s narrator, who certainly doesn’t appear to mean anything offensive by what he says, describes things in a way that seems honest but is nonetheless hilarious. In the “General Prologue,” the narrator describes each of the main characters of The Canterbury Tales, being sure not to leave out even the parts that might be unfavorable, such as the Squire’s lustiness (Norton 1702, lines 79, 95-96), and the Nun/Prioress’ pride (1703, lines 135-137). The irony found in these characters usually has to do with their character traits or actions, which often oppose their positions in society. For instance, though monks are supposed to take a vow of poverty, the Monk in the “General Prologue” of The Canterbury Tales is rich, has hounds, a horse, and hunts like a nobleman of the period (lines 161-203).

In particular, “The Miller’s Tale” is a masterpiece of humor because it is full of jokes that remain funny to this day. This is due to its intended audience, which was everyone from the common man to the nobles. With its affairs of the heart, farts, lies, slander, and mention of literal ass-kissing, “The Miller’s Tale” has all the makings of a reality television show of the modern age. The dramatic irony in the way Nicholas decides to follow Alison’s example by putting his rear out the window, not knowing that Absolom is waiting outside with a hot coulter to brand him, is simply brilliant (Norton 1730-31, lines 512-590). While there have been a few ideas passed around about the moral for this story, ranging from "don't marry a younger person" to "don't fall in love with a married woman," perhaps the best is simply, "do not dangle thine rear out of thine window (or anyone's window for that matter)."

Overall, Chaucer did his darnedest to make everyone feel welcome in his criticism of society. It took him roughly two decades to complete the 24 tales found in The Canterbury Tales--this is surprising considering he had planned to write 100 tales originally (British). However, it was nearly 70 years after Chaucer’s death before the entire compilation of tales was published (British). Whether or not this was due to how scandalous society might have thought his narrative to be, we are left only to ponder. Yet, since the 14th century, we have been reading and studying his amazing work, and this would probably have pleased him very much. After all, he wrote it with such intent and beauty that he spent every year for 20 years writing 850 words on average--that's like an epic poem per year for as long as most average college students have been alive! That's dedication!

.jpg)